The crisp morning air on the beach usually brought with it the joyous barks of Buster, a spirited crossbreed with a coat the color of sun-baked earth. His human, Sarah, a marine biologist with a keen eye for the subtle rhythms of nature, cherished their daily strolls. But this particular Tuesday, a disquieting stillness hung around Buster. He walked with a slight tilt to his head, his usual playful nudges absent. Sarah knelt, her brow furrowed with concern, and gently lifted his floppy ear. What she saw sent a shiver down her spine – a cluster of tiny, pale larvae, writhing almost imperceptibly amidst the matted fur. It was a sight that promised a hidden struggle, a silent invasion that had gone unnoticed until now. The immediate panic gave way to a surge of determination; Buster, her loyal companion, needed help, and she was going to find out how this silent menace had taken root.

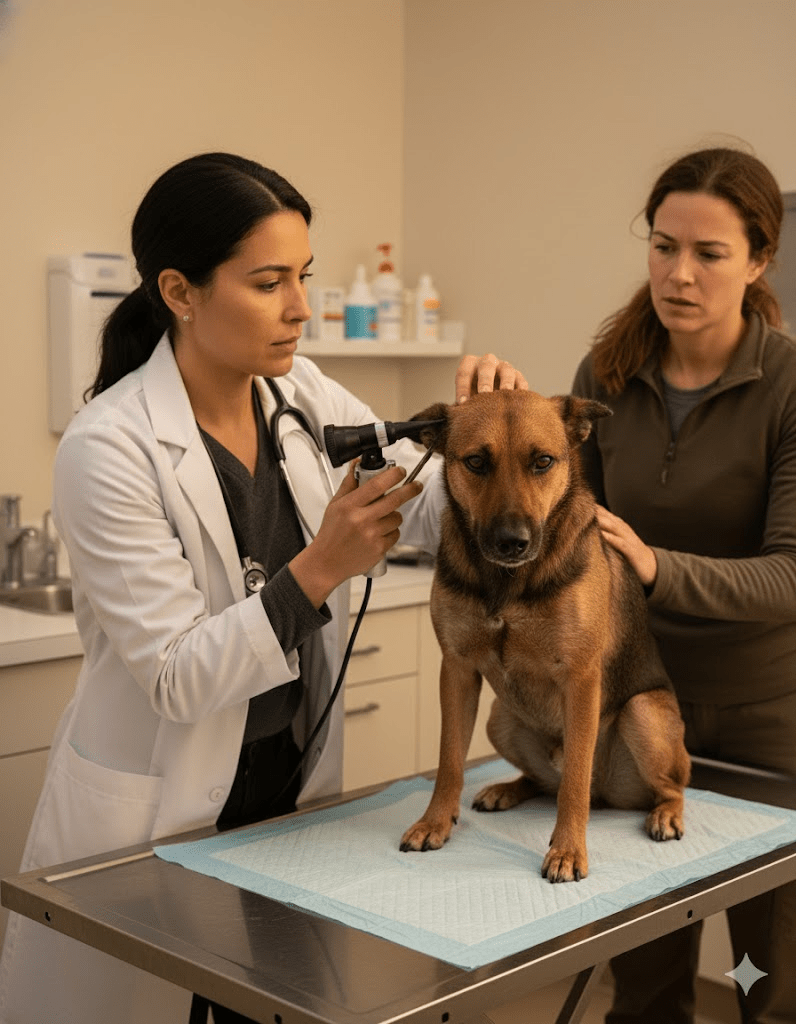

A frantic call to the local vet, Dr. Evelyn Reed, confirmed Sarah’s fears: myiasis, a parasitic infestation by fly larvae. Dr. Reed’s calm voice, however, held a note of intrigue. “These aren’t common housefly maggots, Sarah. The way they’re clustered, the specific site… it suggests something more specialized.” This unexpected detail spurred Sarah’s scientific curiosity, even as her heart ached for Buster. It seemed their beach paradise held secrets, not just in its depths, but right there on its sun-drenched sands.

While Dr. Reed meticulously removed the larvae and cleaned Buster’s ear, Sarah, ever the researcher, began her own investigation. She sent samples of the larvae to a university entomology department, hoping to identify the species. Days later, an email arrived from Dr. Anya Sharma, a renowned expert in insect pathology. The results were startling: Cochliomyia hominivorax, commonly known as the New World screwworm fly. This species was eradicated from North America decades ago, a triumph of veterinary science. Its reappearance, especially on a seemingly isolated stretch of coastline, was a biological anomaly.

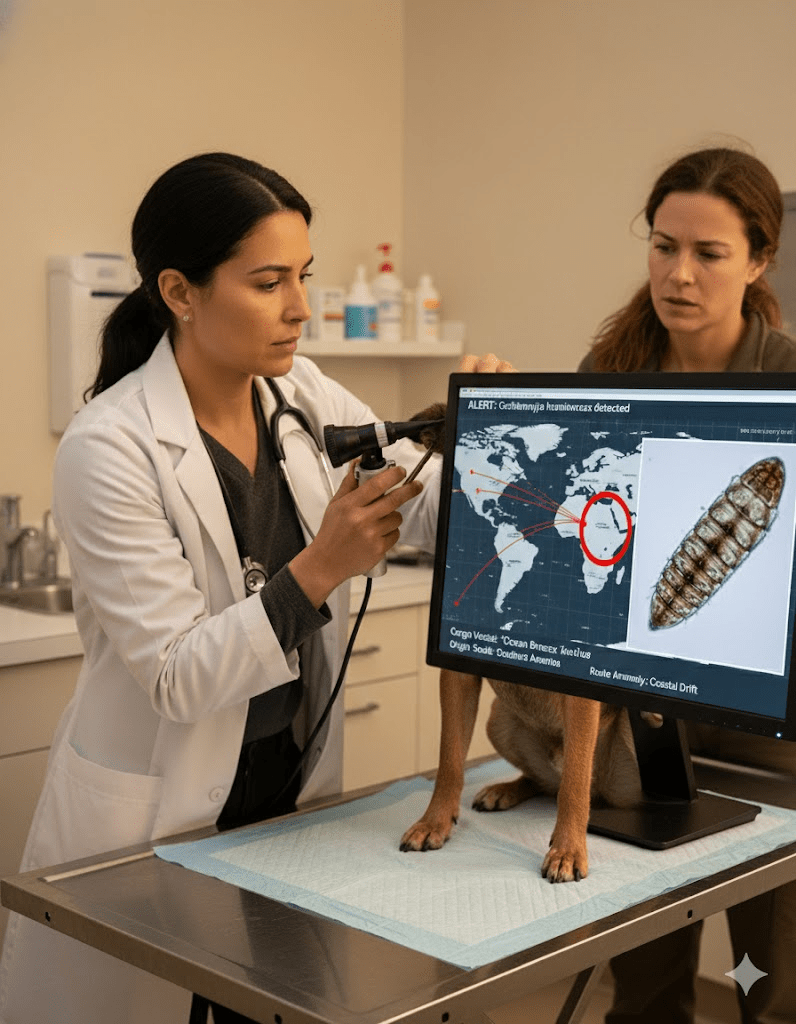

Armed with this knowledge, Sarah and Dr. Reed alerted the authorities. The local agricultural department swiftly launched an investigation, their focus narrowing on a cargo ship that had recently docked, carrying exotic timber from a region where the screwworm was endemic. The vessel had experienced a minor delay offshore due to unexpected currents, keeping it in proximity to their quiet beach for longer than planned. It was a rare, almost improbable confluence of events, a microscopic stowaway carried across oceans by the currents of global trade.

Within weeks, a concerted effort involving government agencies, local veterinarians, and Sarah’s own meticulous observations, led to a swift containment. Traps were set, surveillance increased, and a sterile insect technique – releasing sterilized male screwworm flies to disrupt breeding – was immediately deployed. The scare served as a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of our world and the constant vigilance required to protect our ecosystems from invasive species, even those as seemingly insignificant as a fly. Buster, fully recovered and back to his boisterous self, remained blissfully unaware of the pivotal role his small ear had played in preventing a potential ecological crisis.