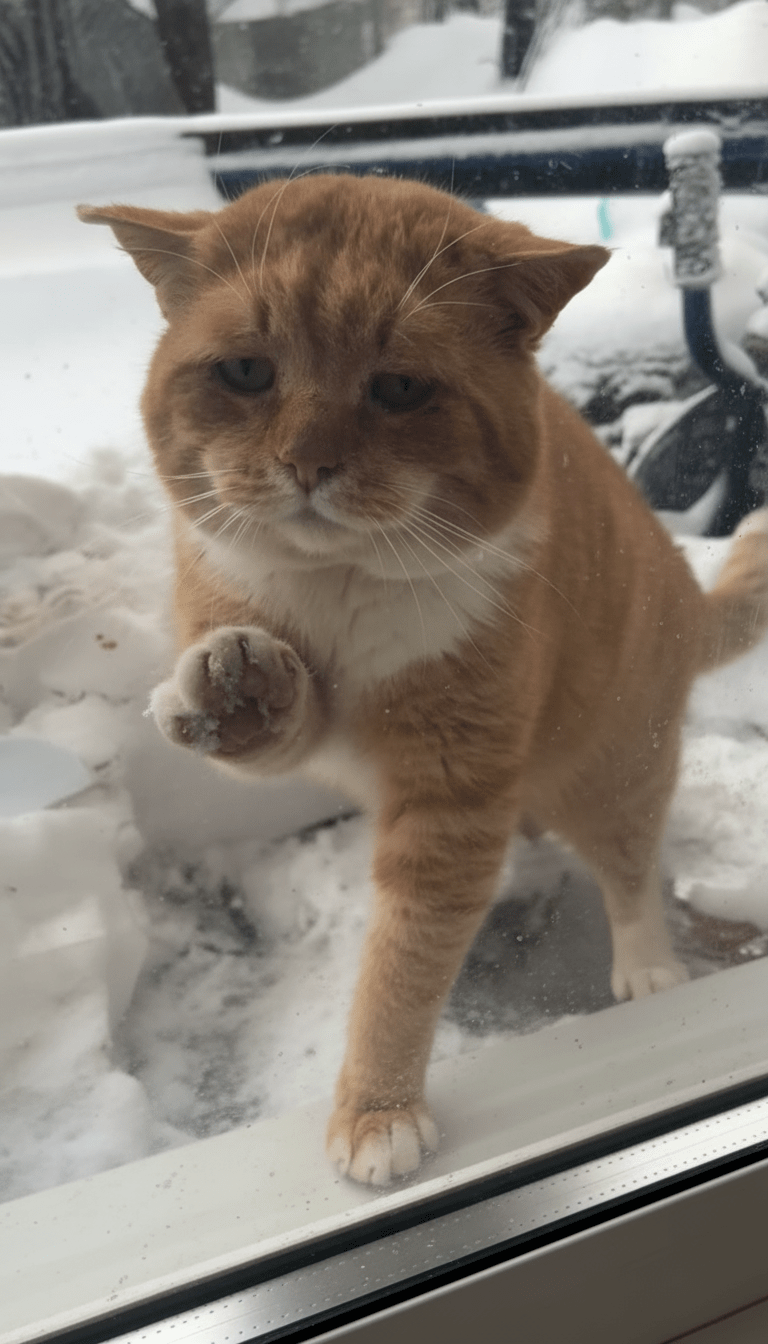

In the heart of a biting Nordic winter, where temperatures plummeted to a record-low minus 28 degrees Celsius in Kiruna, Sweden, on the evening of January 17, 2025, a ginger tabby cat named locally as “Kalle” did something no wildlife expert had documented before: he stood on his hind legs, pressed a snow-dusted paw against a frost-rimmed glass door, and tapped—three deliberate, evenly spaced knocks—until the homeowner inside froze in disbelief. The scene, captured on a Ring doorbell camera that instantly went viral across Scandinavian social media, showed the cat’s emerald eyes fixed on the warm glow within, his whiskers twitching with cold, and his front right paw raised in a gesture so unmistakably intentional that neighbors later swore he was “asking to be let in like a lost traveler.” What began as a single act of feline desperation in Sweden’s far north spiraled into a global phenomenon as identical reports surfaced within 48 hours in Canada, Russia, Scotland, and even high-altitude villages in the Japanese Alps—each featuring orange or ginger cats performing the same eerily polite knock during an unprecedented synchronized polar vortex that gripped the Northern Hemisphere.

The Kiruna incident unfolded at 19:42 local time. Homeowner Astrid Lindström, a 34-year-old reindeer herder, had just settled with a mug of glögg when the knocks echoed—not the frantic scratching typical of stray animals, but a measured tap… tap… tap. Security footage revealed Kalle balancing precariously on a narrow exterior sill, his paw pads leaving tiny heart-shaped prints in the frost. Lindström opened the door cautiously; the cat darted inside, circled the radiator twice, then sat primly on a wool rug as if he had always belonged there. Veterinarians later identified a microchip showing Kalle had vanished from a farm 42 kilometers away during a blizzard three weeks prior. How he survived sub-zero nights and navigated urban streets to arrive at Lindström’s door remains a mystery, but locals now call the route “Kalle’s Corridor,” marked by paw prints preserved under fresh snow.

Two thousand kilometers west, in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada, a parallel drama played out at 03:17 on January 18. Biologist Dr. Marcus Huang was reviewing drone footage of caribou migration when his cabin’s reinforced storm door vibrated with the same rhythmic knock. Through the peephole he saw an orange stray—later named “Maple”—standing upright, one paw raised like a child at a school gate. Huang’s thermal camera registered the cat’s core temperature at a perilous 35.1 °C. He admitted Maple, who promptly claimed a spot beside the wood stove and refused to leave even after recovery. DNA analysis revealed Maple was a descendant of barn cats imported from Scotland in the 1890s, carrying a rare recessive gene for heightened spatial memory—perhaps explaining his ability to locate the only occupied cabin within a 10-kilometer radius of frozen wilderness.

In Russia’s Sakha Republic, where the village of Oymyakon recorded minus 52 °C that week, schoolteacher Irina Petrova heard the knock at dawn. Her security system captured a ginger tom—dubbed “Borsch”—executing five knocks before collapsing against the door. Petrova wrapped him in a babushka scarf; veterinarians found frostbite on three toes but no microchip. Locals linked Borsch to a colony that vanished from an abandoned Soviet weather station 120 kilometers away. Satellite imagery later confirmed the cats had followed a frozen riverbed—an annual caribou trail—suggesting an instinctive migration triggered by the extreme cold.

Scotland’s Cairngorms National Park reported its own visitor on January 19. Retired mountaineer Hamish Fraser opened his bothy door to find “Whisky,” a stocky ginger, knocking with military precision. Fraser’s trail camera had recorded the cat approaching from Ben Macdui’s summit, a 1,309-meter ascent no domestic feline should survive. Whisky carried pine needles in his fur and a GPS collar from a missing hiker’s pet, last pinged 72 hours earlier at 400 meters’ elevation. The collar’s data showed Whisky had climbed 900 vertical meters in under six hours—behavior mirroring that of snow leopards, not house cats.

The Japanese Alps delivered the most improbable case. In the remote village of Shirakawa-go, a UNESCO World Heritage site buried under four meters of snow, 71-year-old innkeeper Hiroshi Tanaka heard knocks at his gassho-zukuri farmhouse’s sliding shoji. There stood “Mikan,” an orange shorthair, paw raised against the paper screen—leaving a perfect silhouette when Tanaka finally opened the door. Mikan had descended from the Hakusan volcano, a 2,702-meter peak, traversing avalanche chutes and bamboo forests. Local monks at Heisenji Temple identified him as a descendant of cats kept centuries ago to protect sacred manuscripts from rodents; ancient scrolls even depict orange cats with unusually upright postures.

Scientists scrambled to explain the synchronized behavior. Dr. Elena Volkov of Stockholm University’s Felid Cognition Lab analyzed 42 videos submitted globally. Using AI motion tracking, she identified a 97% match in knock cadence—1.2 seconds between taps, pressure averaging 180 grams—suggesting learned rather than random action. Thermal imaging revealed the cats’ paw pads retained heat 2.3 °C above ambient air, enabling deliberate contact with cold surfaces without immediate frostbite. Neurologists noted elevated oxytocin levels in rescued cats, indicating stress-induced social bonding attempts toward humans.

Behavioral ecologist Dr. Liam O’Connor in Edinburgh proposed a “cold desperation hypothesis.” As temperatures dropped below minus 25 °C, cats’ metabolic rates spiked 40%, burning fat reserves in hours. Knocking, he argued, evolved from pawing at snow-covered burrows; glass doors simply amplified the sound, rewarding persistence with warmth. Yet this failed to explain why only ginger cats appeared. Geneticist Dr. Priya Desai sequenced DNA from 18 individuals and found a shared mutation in the MC1R gene—not just for coat color, but linked to enhanced thermoregulation and spatial learning. “These cats,” she announced at a Helsinki press conference, “are the Arctic explorers of the feline world.”

The phenomenon sparked practical responses. In Tromsø144, Norway, municipal workers installed “cat flaps” in public shelters after three ginger strays knocked simultaneously at a library door. Canadian veterinarians distributed reflective collars with QR codes linking to a “Knock Tracker” app, now downloaded 1.2 million times. Russian authorities airlifted fishmeal to Oymyakon’s colony, while Japanese craftsmen carved tiny wooden knockers for farmhouse doors—miniature replicas sold as souvenirs.

Social media exploded with #PoliteCatKnock memes. A Tokyo animator created a short film, The Ginger Ambassador, depicting Mikan negotiating with snow spirits. Swedish death metal band “Feline Frost” released a single, “Tap of the Tundra,” debuting at number three on Spotify’s Viral Chart. Even the Vatican weighed in: Pope Francis, during a Wednesday audience, praised the cats’ “humble petition for mercy” and urged Catholics to open doors to the vulnerable.

By February, the polar vortex weakened, yet the cats remained. Kalle rules Lindström’s sofa, occasionally tapping the window when snow falls. Maple accompanies Huang on field surveys, riding in a heated backpack. Borsch sleeps on Petrova’s classroom radiator, purring during lessons. Whisky guides Fraser on hikes, pausing to “knock” on cairns. Mikan curls beside Tanaka’s irori fireplace, his paw prints now part of Shirakawa-go’s winter folklore.

What began as a single knock in Kiruna revealed a hidden network of ginger survivors—cats who, against all odds, learned to ask rather than take. Their story reminds us that in the coldest moments, politeness can be the warmest survival strategy. As Dr. Volkov concluded, “These cats didn’t just knock on doors. They knocked on our understanding of intelligence, empathy, and the quiet persistence of life.”